What is our fundamental need? According to Andy Crouch, it’s to be recognized by God and each other. This need is so important that studies have shown when we are neglected of it, we don’t develop properly. In the Book, The Life We’re Looking For: Reclaiming Relationship in a Technological World, Andy Crouch starts by laying out this need before addressing how we’re failing to fulfil it and how we might address it in the future.

As someone who loved The Tech Wise Family by Andy and who has become increasingly technologically wary, I was excited to read Andy’s book. It was both more than I expected, and very different than what I had expected.

Important note: Andy is writing from a Christian perspective and this is one I hold. His worldview influences his writing heavily.

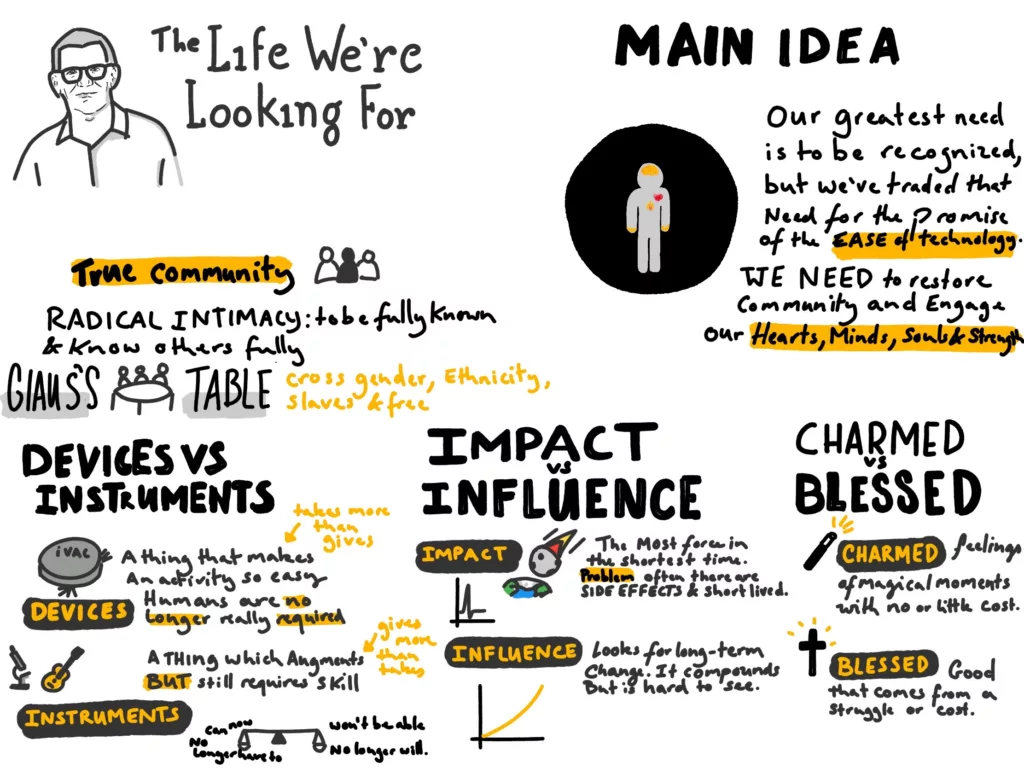

The Life We’re Looking For Sketchnote

The main point

Andy’s main point is that we’re increasingly trading real relationships, with each other and God, for the “magic” of technology. This isn’t completely new but recent changes in the world from the industrial, financial and telecommunication revolutions have made this view dominant in society.

Andy contends that to be truly satisfied, we need to promote a society where we are fully human and in true relationships with God and each other. This means we need to engage our

- Hearts

- souls

- minds

- strengths

and recognize each other as being of immense worth, no matter of our differences.

The search for true relationships and a lesson from Gaius’s Table

To give an example of true relationship, Andy highlights the community in the background of Paul’s letter to the Romans.

This group of slaves and free people, men and women, Jews and gentiles met in the house of Giaus, a wealthy roman head of household. Here, although they were treated very differently by society, they were all equal.

One of the shocking details Andy picks up on is that the person who writes Paul’s letter, Tertius, has a slave name for “3rd”.

By society he was viewed of so little importance that he was merely denoted by the order of his birth. And yet Paul invited him to add his name to the letter, showing him of as equal importance as Giaus.

This kind of relationships, where we see and value even the people neglected by society, is what Andy argues for.

Devices vs instruments

A core point Andy distinguishes is between devices and instruments. Andy defines them as

A device is something with makes an activity so easy, that humans are no longer really required. An example is how a roomba can tidy up the house with no human effort.

This seams like it’s an unqualified good; we no longer have to do a boring, time consuming or difficult task. However, there are usually unforeseen consequences of devices.

We usually adapt for our devices.

Using the Roomba examples, we might design our homes so they are more suitable for our robot friends to clean. Or the unlimited access we now have with the internet can lead to us watching endless entertainment rather than engaging deeply with what we watch.

Instruments, on the other hand, still augment our skills or abilities but require skill (and usually focus) to use. The main example Andy gives is a bike which allows a person to travel further than by foot, but still engages the senses and requires strength. Going for a bike ride might leave you tired, but often it comes with a sense of achievement. Compare that to the experience of a long-haul flight; you can travel further than ever possible in a short time, but you sit passively the whole time.

Does it give more than it takes?

A key question to our evaluation of the tools around us is if they give more than they take.

An instrument will allow us to do new things without imposing new requirements or constraints upon the user. A great instrument also empowers us to more fully use our hearts, souls, minds and strength and deepen relationships.

In contrast, a device will impose more limits than benefits and reduce us as

Impact vs influence

Personal note: Using “impact” as a verb is one of my pet peeves and has been for a while. So I was delighted to see Andy has similar issues with it.

He points out how recent this usage of the word is, and how there are many other options including influence. I’d go further and say that every other near synonym is more expressive than impact. Andy does, however, point out why impact has become a popular verb: it reflect quick, significant change.

In our current society, the goal of “moving fast and break things” is lauded. Caution is a negative and so any negative side effects are seen as costs of innovation.

But impact is short lived, and so another impact is required. And then another and another. All the while the shockwaves of these impacts can be causing colossal damage. Just look at the data around self-esteem and use of Instagram all the while the owners try to make it more addictive.

The alternative is influence, which looks at long-term change and compounding effects. It’s not about making massive changes now, but about deliberate movement towards a goal.

Influence isn’t as popular as it can often be missed in the moment. Contrast that with impact and it’s easy to see results. But in the long run, impact leads to burnout and influence leads to growth.

Charmed vs blessed

A final key difference is between charmed and blessed.

Andy highlights how many of the examples we might tag on social media as #blessed are really examples of living a charmed existance.

A charmed existence is one free of worry, pain and work.

It’s the all inclusive holiday in the sun where we don’t lift a finger and all our needs are catered for. Sounds wonderful doesn’t it, but there are negatives.

Charm is costly. It’s not just money, it can be costly in terms of personhood. To keep a charmed lifestyle for some, others have to live in servitude. Yes, tourism can help raise economic standards in some places (while making them dependent) but it isn’t always equal and costs still need to stay low to keep that servitude possible.

Furthermore, the relationship between the charmed person and the server isn’t one of equals. It’s one of subjugation via economics.

The contrast is a blessed existance, one which is rich in love but is costly too.

Andy draws examples of Biblical figures such as Abraham, Jacob and Jospeh who are blessed but after suffering or through suffering. He even draws on his own story of his friend dying of cancer and how although it was immensely painful, it was also a blessing to be able to be so close with him.

Conclusion

Andy isn’t against technology; he even owns a Roomba (something I surely would have thought to be a device he’d be cautious of). So this book isn’t a doom and gloom or quick easy practical tip book.

At first I felt slightly disappointed by this fact. After all, I want help and guidance to help avoid the negatives of technology and devices. But I realised that this actually helps prove the point of the book.

The real challenge isn’t just reducing our technology dependency, but replacing it with pursuing true relationships. That’s not something with easy prescriptions for every situation, instead it’s something we all need to workout on our own, for our contexts.

Plus there are plenty of blogs and books on how to reduce our technological dependence.

Grab your own copy of The Life We’re Looking For: Reclaiming Relationship in a Technological World

If this review has whet your appetite, then you should pick up your own copy of Andy’s book to go into greater depth. And if you’d like some practical tips as a parent, I’d recommend his book The Tech Wise Family

Leave a Reply