“Do more of what works” is a great principle, but it has its limits. That’s the core insight of the Law of Diminishing Returns. But this mental model has more depth to it than just a simple truism. It can be applied to a wide range of fields to avoid wasting your efforts.

In this short post, I’ll share what it is, why it matters and how you can use it in your life (along with a few simple sketches to bring the ideas to life).

What Is the Law of Diminishing Returns?

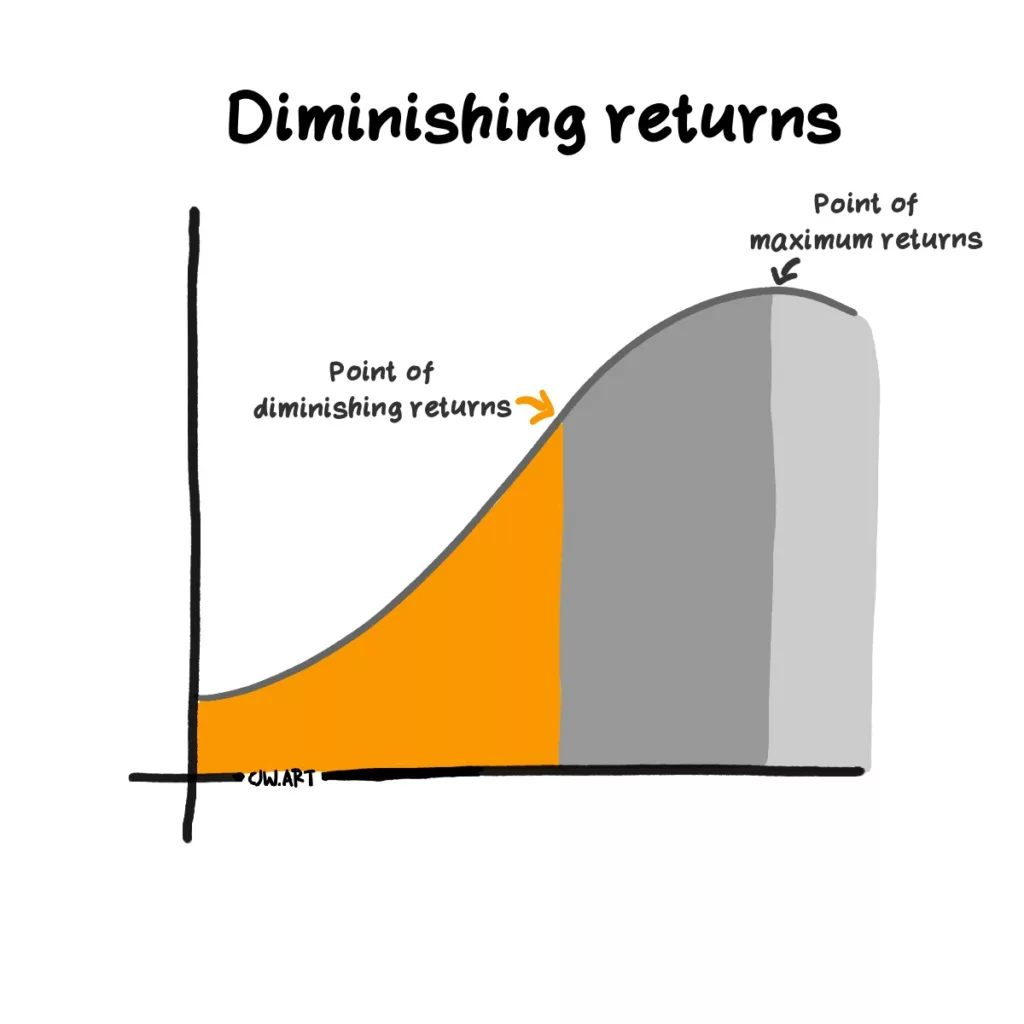

Diminishing returns is an economic principle stating that after a certain point, adding more input (money, time, effort, etc) will produce smaller improvements. In extreme cases, it can actually reduce the output or make things worse.

Here’s a simple economic example.

If you make chocolate, the more you produce, the more you can sell and so the more profit you will make. However, there’s a limit to the amount of chocolate people actually want to eat, and you have to compete against other brands. Rather than being a hard limit where you suddenly don’t make any additional profit, you’ll see reduced returns and then might actually make less profit as you’ll waste money on products that aren’t consumed.

But the law of diminishing returns doesn’t just apply to economics, it’s a mental model that can apply to:

- Productivity — You can only spend so long working on something before you become tired (diminishing returns) and eventually burnout (negative returns).

- Fitness — Like productivity, working out too hard can lead to exhaustion and even injuries.

- Marketing — At first, the more you pay for paid ads, the higher the returns you’ll see, but after a certain point, paying more will display the same ads to the same people leading to diminishing returns.

Why Does It Matter?

Understanding diminishing returns helps us avoid wasting our efforts and allocating our resources effectively. It functions similarly to the 80/20 principle, by identifying where the point of diminishing returns is, we can achieve the highest leverage for our actions.

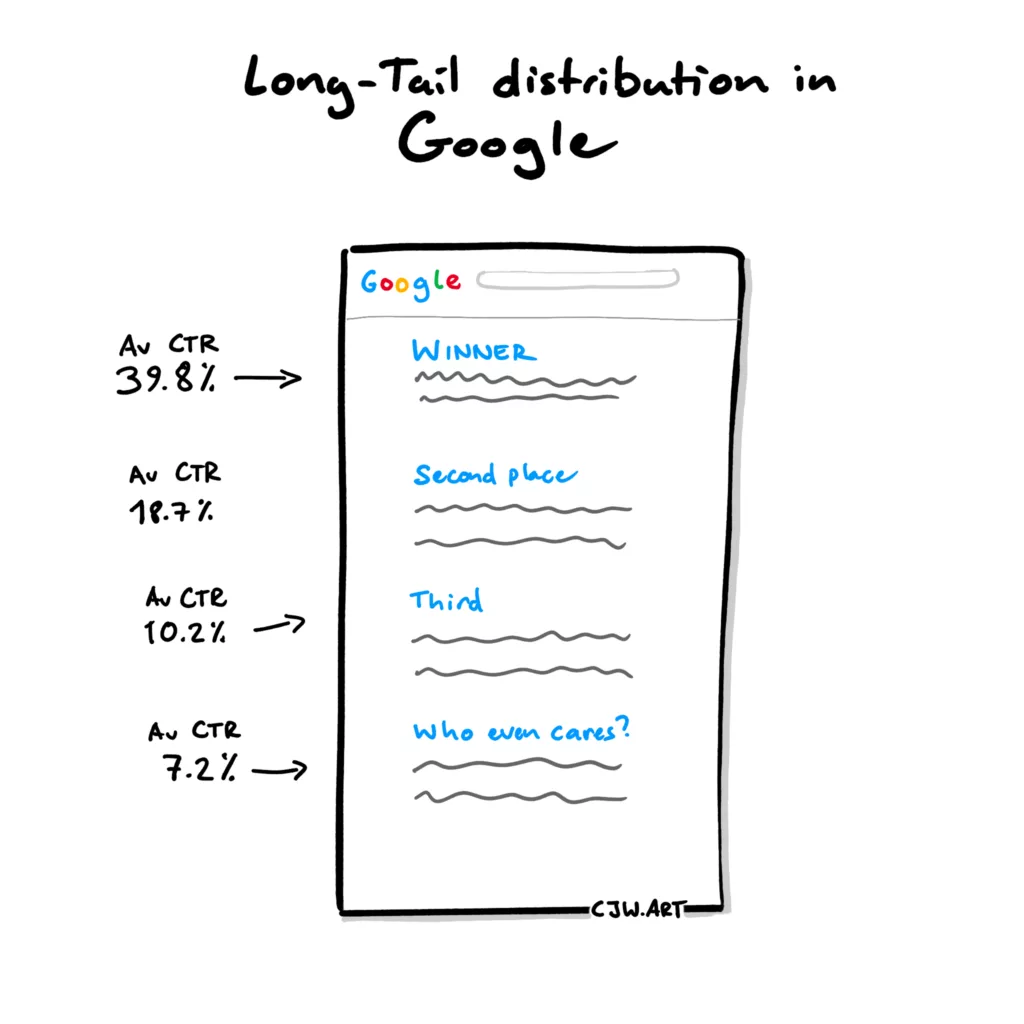

In rare cases, it may be worth investing more to benefit from the marginal gains that come after the point of diminishing returns. For example, finite games where there is one winner or loser. Similarly, there may be long-tail distributions where achieving a small increase in one metric leads to massive returns from another.

A classic example is SEO, where the top result can get millions more clicks than even the second result.

But here are a few more examples where you might want to apply the principle.

Learning a new skills

This was made famous in Josh Kaufman’s book The First 20 Hours.

Most skills have a few core components that will get you 80% of the way. For example, if you are able to play four chords on the Ukulele, you can play almost any basic pop song.

By targeting the right skills and reaching the first 20 hours point, you then have a solid foundation to keep learning.

The goal isn’t to become a 10,000-hour expert, but enough to keep growing your skills.

Time management

“Is it worth spending another hour on this project?”

Many creatives suffer from perfectionism. They get 95% done but never progress any further as they constantly tweak, tweak again, go back to the second version and then get distracted by another new project.

When you use the principle of diminishing returns, you can make a better decision whether you should keep tweaking or stop.

This can be an effective buttress against Parkinson’s law as for most of us it isn’t worth targeting the marginal gains that come from obsessing over the diminishing returns.

How to Apply the Law of Diminishing Returns

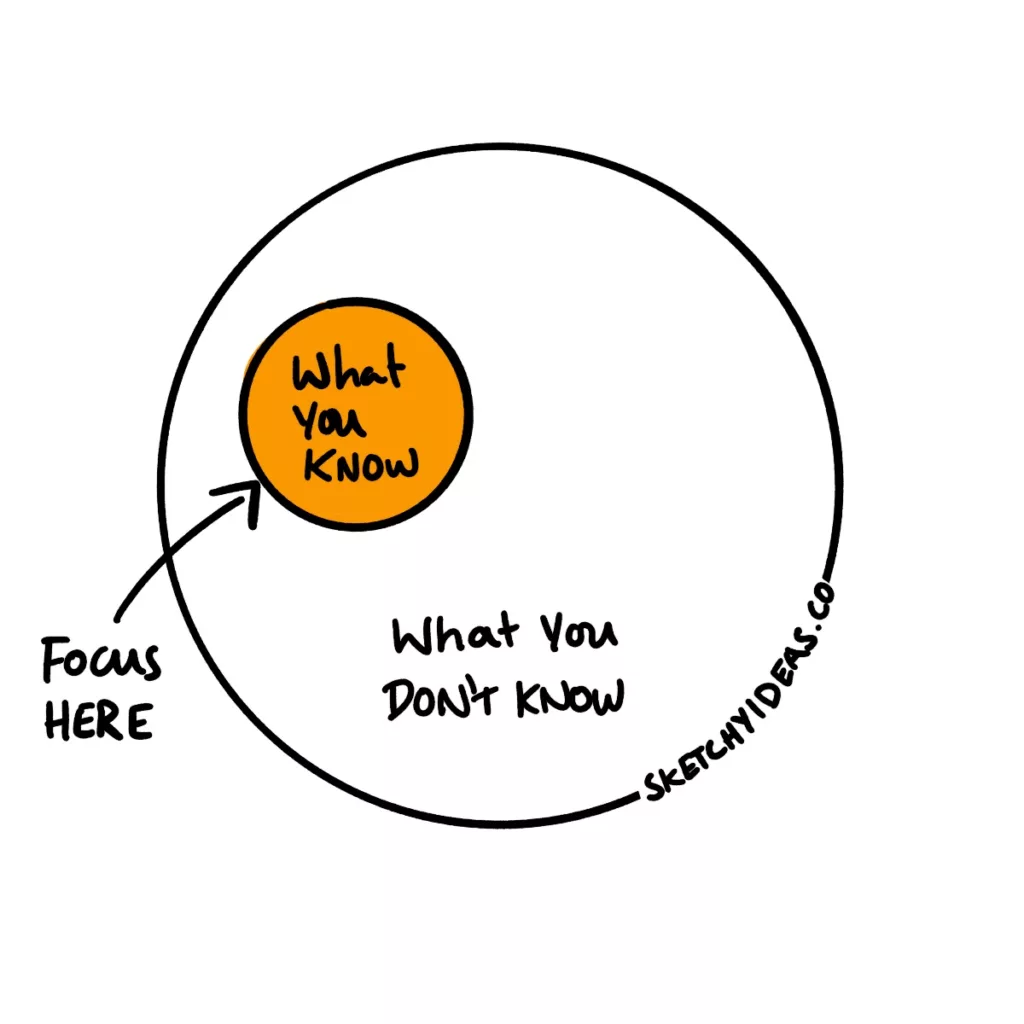

The first step is to acknowledge whether you’re in a known field or an unknown field.

If this is an area where you have data and experience, you can estimate the point of diminishing returns upfront. For instance, let’s say you are going to write a paper for university. You can probably remember how long you spent researching, writing and editing your last one. You can probably also remember how much time felt wasted (or perhaps how you’d wished you’d read one extra book on the topic!)

With those reflections, you can make some data-informed actions.

- Set cut-off points — Guestimate when the point of diminishing returns is and use that to guide your cut-off point. When you are starting out, you might want to add some extra margin.

- Identify high-leverage actions — Prioritise the few actions that bring the highest returns during that time.

- Monitor and adjust — Notice what the actual outcomes are and adjust your thresholds based on your results.

If you are coming into a new field, let’s say running your first paid ads for your business, you won’t have the benefits of past experience. Instead, you can use other people’s experience or advice from experts to set your first prediction.

But in some cases, you just have to test and see, collecting your own data before adjusting.

Conclusion

There’s no simple answer to how much you should invest in any particular endeavour, but the law of diminishing returns can help you make a more informed choice. Sometimes it’s worth the cost to secure more marginal gains, other times it’s not. But knowing when you’ve crossed the point is vital.

Is there an area of your life where you’re sinking extra effort for no benefit?

Leave a Reply